I never understood all the fuss about that old riddle—“If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear, does it still make a sound?” Isn’t it just a question of how we choose to define the word sound? If we mean “vibrations of a certain frequency transmitted through the air,” then the answer is yes. If we mean “vibrations that stimulate an organism’s auditory system,” then the answer is no.

More challenging, perhaps, is the following conundrum sometimes attributed to defiant educators: “I taught a good lesson even though the students didn’t learn it.” Again, everything turns on definition. If teaching is conceived as an interactive activity, a process of facilitating learning, then the sentence is incoherent. It makes no more sense than “I had a big dinner even though I didn’t eat anything.” But what if teaching is defined solely in terms of what the teacher says and does? In that case, the statement isn’t oxymoronic—it’s just moronic. Wouldn’t an unsuccessful lesson lead whoever taught it to ask, “So what could I have done that might have been more successful?”

That question would indeed occur to educators who regard learning—as opposed to just teaching—as the point of what they do for a living. More generally, they’re apt to realize that what we do doesn’t matter nearly as much as how kids experience what we do.

Consider what happens between children and parents. When each is asked to describe some aspect of their life together, the responses are strikingly divergent. For example, a large Michigan study that focused on the extent to which children were included in family decisionmaking turned up different results depending on whether the parents or the children were asked. (Interestingly, three other studies found that when there is some objective way to get at the truth, children’s perceptions of their parents’ behaviors are no less accurate than the parents’ reports of their own behaviors.)

But the important question isn’t who’s right; it’s whose perspective predicts various outcomes. It doesn’t matter what lesson a parent intended to teach by, say, giving a child a “timeout” (or some other punishment). If the child experiences this as a form of love withdrawal, then that’s what will determine the effect. Similarly, parents may offer praise in the hope of providing encouragement, but children may resent the judgment implicit in being informed they did a “good job,” or they may grow increasingly dependent on pleasing the people in positions of authority.

From both punishments and rewards, moreover, kids may derive a lesson of conditionality: I’m loved—and lovable—only when I do what I’m told. Of course, most parents would insist that they love their children no matter what. But, as one group of researchers put it in a book about controlling styles of parenting, “It is the child’s own experience of this behavior that is likely to have the greatest impact on the child’s subsequent development.” It’s the message that’s received, not the one that the adults think they’re sending, that counts.

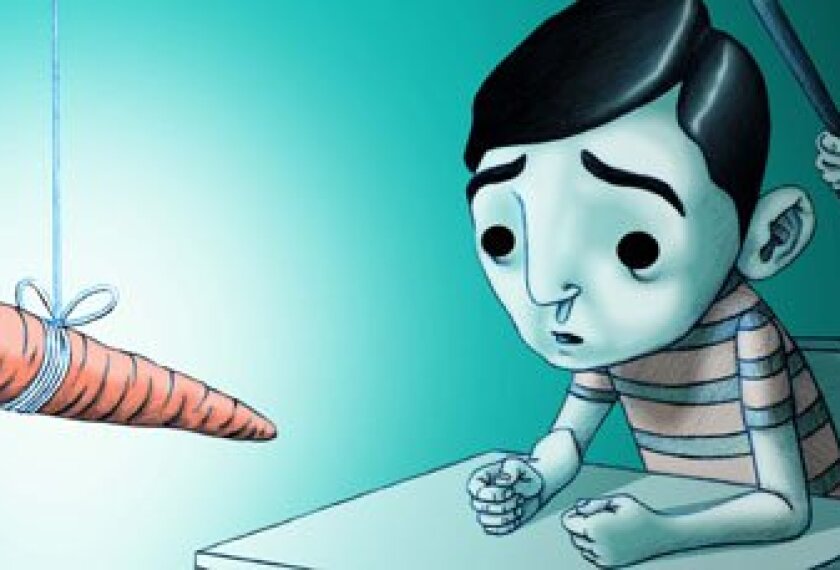

Exactly the same point applies in a school setting, since educators, too, may use carrots and sticks on students. We may think we’re emphasizing the importance of punctuality by issuing a detention for being late, or that we’re making a statement about the need to be respectful when we suspend a student for yelling an obscenity, or that we’re supporting the value of certain behaviors when we offer a reward for engaging in them.

But what if the student who’s being punished or rewarded doesn’t see it that way? What if his or her response is, “That’s not fair!” or “Next time I won’t get caught” or “I guess when you have more power you can make other people suffer if they don’t do what you want” or “If they have to reward me for x, then x must be something I wouldn’t want to do”?

It’s tempting, when students are given some kind of assessment, to assume the results primarily reveal how much progress each kid is, or isn’t, making—rather than noticing that the quality of the teaching is also being assessed.

We protest that the student has it all wrong, that the intervention really is fair, the consequence is justified, the reward system makes perfect sense. But if the student doesn’t share our view, then what we did cannot possibly have the intended effect. Results don’t follow from behaviors, but from the meaning attached to behaviors.

The same is true of teachers who are stringent graders. Their intent—to “uphold high standards” or “motivate students to do their best”—is completely irrelevant if a low grade is perceived differently by the student who receives it, which it almost always is. Likewise, if students view homework as something they can’t wait to be done with, it doesn’t matter how well-designed or valuable we think those assignments are. The likelihood that they will help students learn more effectively, let alone become excited about the topic being taught, is exceedingly low.

If teachers just do their thing and leave it up to each student to make sense of it—“so that the child comes to feel, as he is intended to, that when he doesn’t understand it is his fault” (to borrow John Holt’s words)—then meaningful learning is likely to be in awfully short supply in those classrooms.

But let’s face it: It’s easier to concern yourself with teaching than with learning, just as it’s more convenient to say the fault lies with people other than you when things go wrong. It’s tempting, when students are given some kind of assessment, to assume the results primarily reveal how much progress each kid is, or isn’t, making—rather than noticing that the quality of the teaching is also being assessed.

“I taught a good lesson ...” probably suggests that learning is viewed as a process of absorbing information, which in turn means that teaching consists of delivering that information. (Many years ago, the writer George Leonard described lecturing as the “best way to get information from teacher’s notebook to student’s notebook without touching the student’s mind.”) This approach is particularly common among high school and college teachers, who have been encouraged to think of themselves as experts in their content areas (literature, science, history) rather than in pedagogy. The reductio ad absurdum would be those who “took their content so very seriously that they forgot their students,” as Linda McNeil put it in her devastating portrait of high school, Contradictions of Control: School Structure and School Knowledge.

The trouble may start in schools of education, where preservice teachers in many states spend very little time learning about learning, relative to the time devoted to subject-matter content. Worse, when teachers these days are told to think about learning, it may be construed in behaviorist terms, with an emphasis on discrete, measurable skills. The point isn’t to deepen understanding (and enthusiasm), but merely to elevate test scores.

The fact is that real learning often can’t be quantified, and a corporate-style preoccupation with “data” turns schooling into something shallow and lifeless. Ideally, attention to learning signifies an effort to capture how each student makes sense of the world, so we can meet them where they are. “Teaching,” as Deborah Meier has reminded us, “is mostly listening.” (It’s the learners, she adds, who should be doing most of the “telling,” based on how they grapple with an engaging curriculum.) Imagine how American classrooms would be turned inside out if we ever really put that wisdom into action.

And it’s not just listening in the literal sense that’s needed, but the willingness to imagine the student’s point of view. How does it feel to be sitting there with your shaky efforts to write an essay or solve a problem subjected to continuous evaluation? (Many teachers who expect their students to bear up under, and even benefit from, a constant barrage of criticism are themselves often extremely sensitive to any suggestion that their craft could be improved.) Indeed, educators ought to make a point of trying something new in their own lives, something they must struggle to master, in order to appreciate what their students put up with every day.

Finally, as teachers are to students, so administrators are to teachers. Successful school leadership doesn’t depend on what principals and superintendents do, but on how their actions are regarded by their audience—notably, classroom teachers. Those on the receiving end may be older than students, but the moral is the same: It’s best to see what we do through the eyes of those to whom it’s done.